Introduction

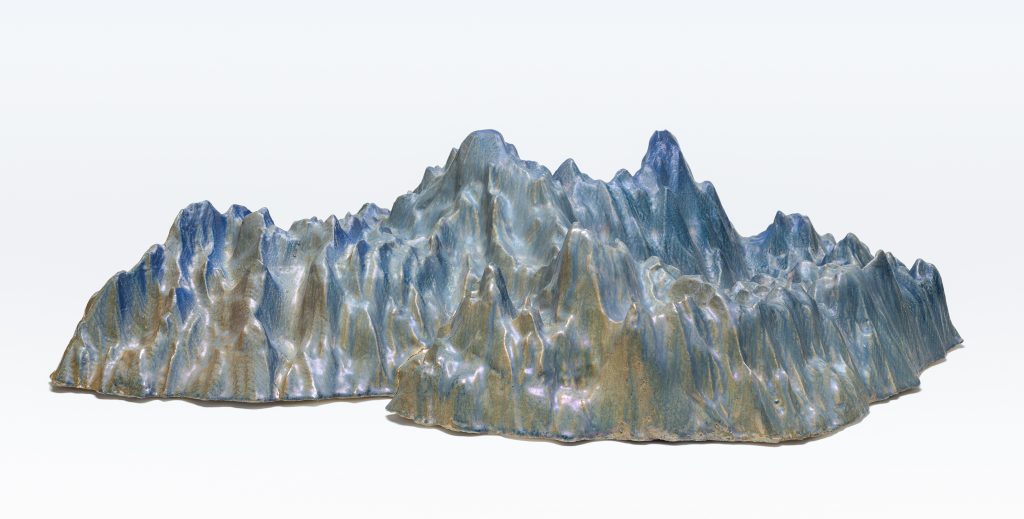

This exhibition included eight mural-size watercolors and eight sculptures—four sculptures cast in ceramic and four cast in glass. In the watercolors and the sculptures the octopus is camouflaged within the wave pattern of the sea. The glass and ceramic sulcptures were generated through a three-dimensional computer program to raise and lower the pattern in the watercolor drawings.

Curated by Loretta Yarlow

Catalog available with essay by John Yau.

Glass fabrication: Ross Art Studios

Installation Views

Individual Works

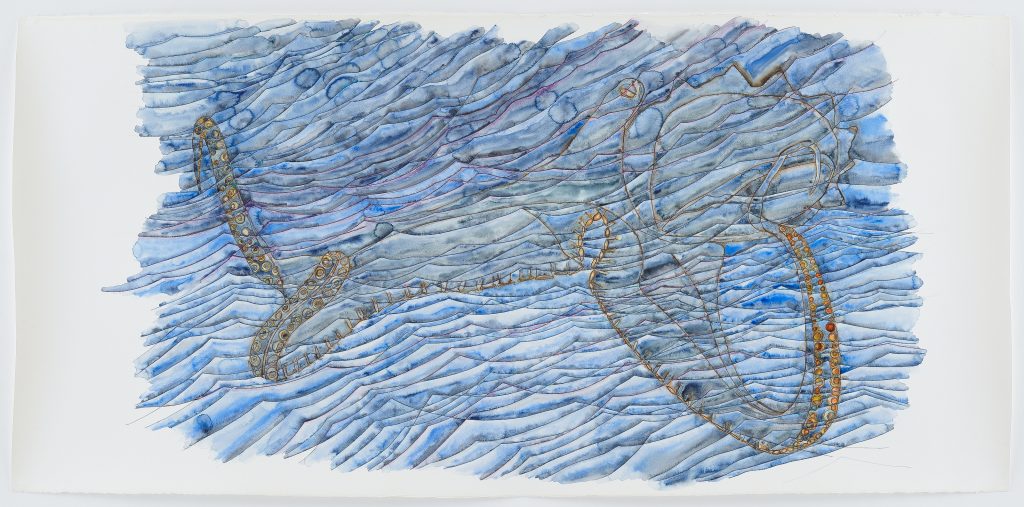

Morning Octopus, 2013, watercolor on paper, 60-1/2 x 95-3/4 inches (153.7 x 243.2 cm)

Morning Octopus, 2014, ceramic with iridescent luster, 27-3/4 x 8 x 4 inches

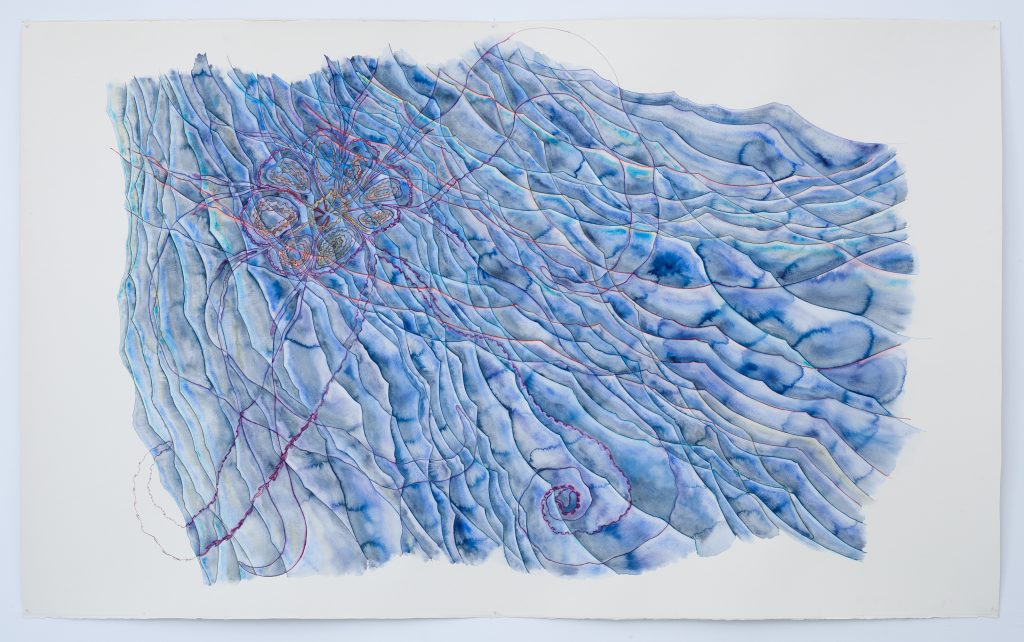

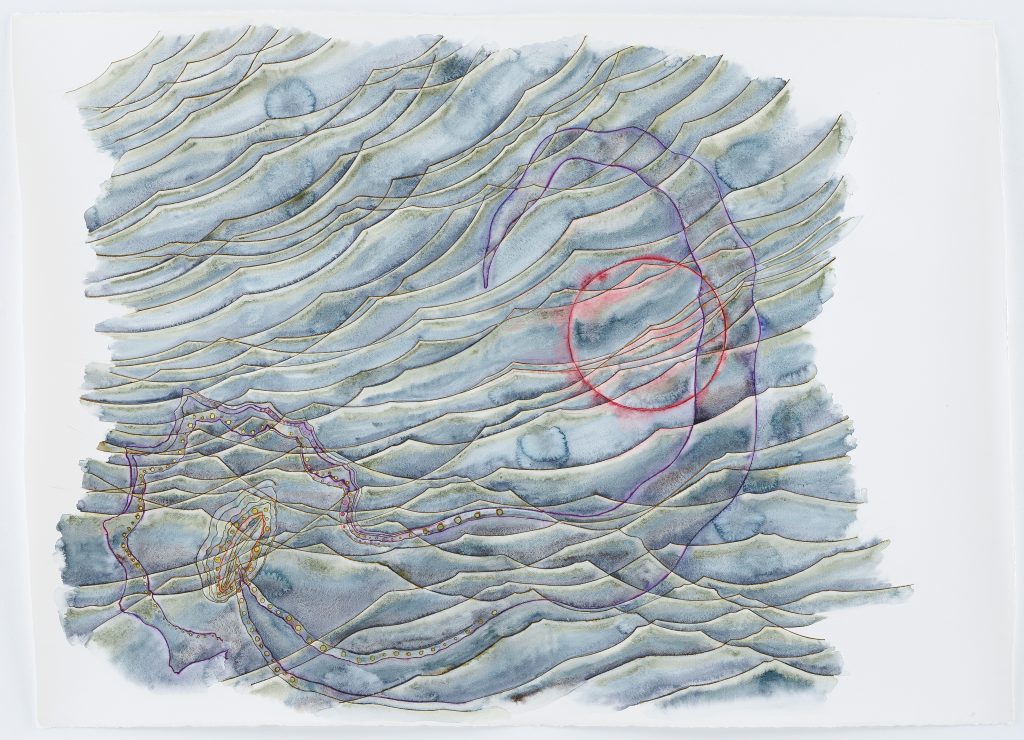

Moving in a Purple Sea, 2011, watercolor on paper, 51 x 90 inches (129.5 x 228.6 cm)

Moving Octopus in a Purple Sea, 2014, lead crystal, 40 x 35 x 12 inches

Red Edge in Shallow Water, 2012, watercolor on paper, 60-3/4 x 102 inches (154.3 x 259.1 cm)

Hiding Octopus in Shallow Water, 2014,glazed ceramic, 38 x 14 x 9-1/2 inches

Split Octopus, 2011, watercolor on paper, 51 x 107 inches (129.5 x 271.8 cm)

Split Octopus, 2013, lead crystal, 7 x 15 x 36 inches

Predator, 2012, watercolor on paper, 60-1/2 x 99 inches (153.7 x 251.5 cm)

Predator, 2014, ceramic with iridescent luster, 27 x 20 x 7-1/2 inches

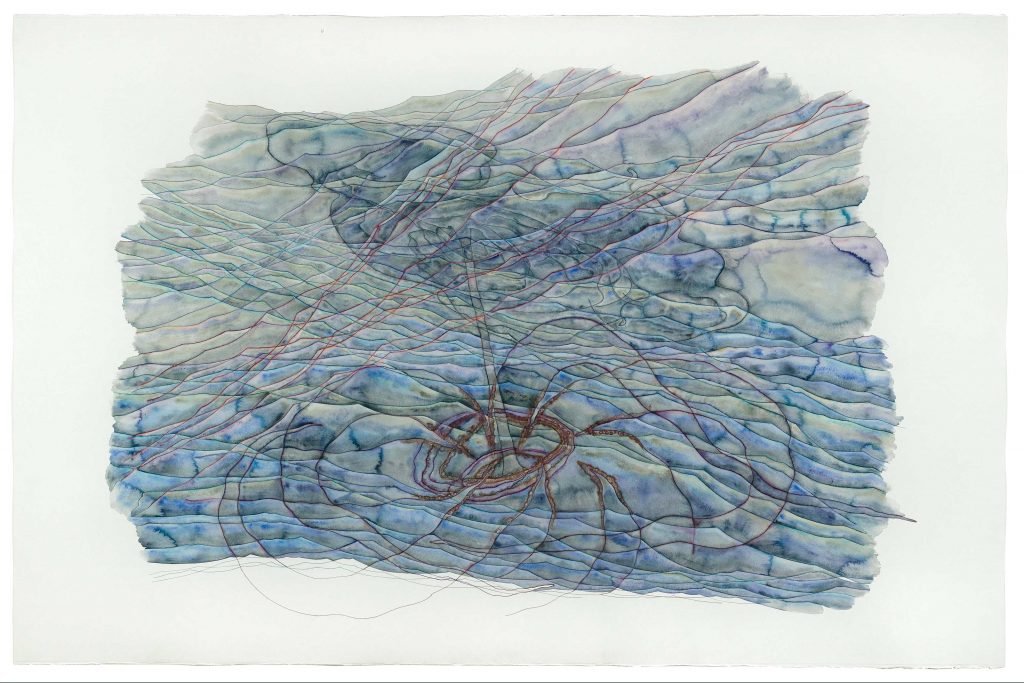

Lurking Octopus, watercolor on paper, 51 x 99-1/2 inches (129.5 x 252.7 cm)

Lurking Octopus, 2013, lead crystal, 9 x 34-1/2 x 10 inches

Octopus with Black Ink, 2014, watercolor, 60–3/8 x 95–1/4 inches

Octopus in a Cloud of Black Ink, 2013, lead crystal, 8-1/2 x 31-1/2 x 9-1/2

Sleeping Octopus Under a Red Moon, 2011, watercolor on paper, 51-1/4 x 70-1/4 inches (130.2 x 178.4 cm)

Sleeping Octopus in Murky Water, 2014, glazed ceramic, 25 x 12-1/2 x 5-1/2 inches

Catalog

The Artist as octopus | John Yau

Katy Schimert’s installation, Camouflage, Ink, and Silence, consists of eight large watercolors that measure as high and wide as 100 x 60 inches, as well as eight corresponding ceramic and glass sculptures mounted on low pedestals. Once we enter it we realize that we have entered an underwater environment, that we have gone—metaphorically speaking—below the surface. The subject of each watercolor is a large octopus floating beneath the waves’ faceted surface, while the craggy sculptures evoke the terrain of the ocean floor. The often transparent octopus might be sleeping, hunting its prey, or stealthily moving through the morning sea. The relationship between the octopus and the ocean in which it is floating is ever in flux. At the same time, Schimert does not completely cover the white expanse of the paper with watercolor. Bounded by a contour that can be precise or ragged, her fragment of the ocean is suspended within the white paper’s borders. By underscoring the fragmentary nature of her subject, the artist is able to infuse her segments of the ocean with a contradictory identity; they are both liquid and solid, as if they were pieces of colored glass in which the octopus has been preserved. This duality is integral to both our experience of Schimert’s installation and the meaning of the work. In some of the watercolors, such as Morning Octopus (2013), the artist employs a sinuous line to distinguish the creature from the faceted waves above. In Moving in a Purple Sea (2011), the creature’s contours are barely discernible from the striations defining the ocean’s multi-sectioned surface. Looking becomes an act of refocusing, of picking out a line and tracing it until our eyes complete the form, differentiating it from its environment. Of course, this becomes complicated because the octopus is not a simple form: besides its eight highly flexible tentacles, it is known for its ability to camouflage itself, to become nearly identical to its surroundings. When that happens, looking becomes a kind of excavation as we sift through the visual data, checking it against what we know. While filtering is not the only kind of looking that Camouflage, Ink, and Silence invites viewers to bring to bear, it is certainly one of the most intriguing.

The octopus has long been a subject of fascination and speculation for writers and artists, ranging from Jules Verne, Herman Melville and Marianne Moore, to Hokusai, Pablo Picasso and Steve DiBenedetto. Working in very different forms—writing and art—each of these individuals developed a particular mythology regarding the octopus. For Verne and Melville, it can be destructive, a harbinger of death, while for Hokusai, it was erotic, a bringer of pleasure. The elusiveness of the octopus is part of its mystique. But this is only part of the story. There are also the creature’s unique physical characteristics—an oversized head from which extend eight tentacles (or arms) lined with suckers. Finally, there is the dense cloud of ink that the octopus can release into the ocean, enabling it to escape from danger.

Schimert’s octopus is an expansive vision of the artist, who, in this case works in watercolor and ceramics. It is a stand-in for the creative spirit, and the bonds that tie destruction, camouflage and creativity together in an ongoing process. The octopus becomes a focal point of Schimert’s meditation on the relationship of her materials (watercolor, ink, ceramics and glass) to her processes (drawing, staining, casting, heating and cooling). This is why the act of looking as a form of excavation is integral to our experience and understanding of Camouflage, Ink, and Silence. We not only excavate the form, but we also reflect upon its identity as a solid or transparent thing, as something made out of dried swatches of colored water.

Schimert isn’t satisfied by either an art that is purely visual, if such a thing was even possible, or by one that is essentially social in its concerns. The kind of seeing she is after connects looking outward with looking inward, the gaze merged with reflection. It is an act done in solitude, just as her octopus exists alone in the sea. Furthermore, the question she asks is a fundamental one: what is an artist? Rather than asking, why make art, which is likely to be more socially motivated, fraught with questions of whether art can change people’s lives, she wants to get at something more basic. For all of its human-like qualities, the octopus is other. As the poet Arthur Rimbaud famously wrote to his friend George Izambard on May 13, 1871: “Je un autre” (I is another).

Schimert uses a fine line to divide the constantly changing ocean surface into a series of unique striations, which fit tightly together to form a large, rough-edged, slab-like image, as in Lurking Octopus (2010) and Predator (2012). Within the ocean’s linear rhythms she embeds the contour of an octopus, whose tentacles may extend out or fold in, like an umbrella. The composition of the ocean and octopus requires that she fill in each section individually, carefully applying the watercolor, so that it becomes a stain of color. In order to ensure that she keeps track of the relationship between each part and the whole, as well as part-to-part, she must stay in control of the tonality she applies to each section while paying close attention to its relationship to the adjacent sections. And yet, she must also trust chance, because she is not simply filling in each section in some paint-by-numbers manner. This constant interplay between control and chance is certainly one of the marvels of Schimert’s watercolors.

In Lurking Octopus, for example, the sharp-edged, elongated sections of the ocean’s surface slant down from the upper right toward the lower left corner. Dusky streaks of pink evoke the passing reflection of the setting sun across the turbulent sea. While the ocean’s currents and undulating surface are effectively captured by the painting’s swarming lines and cresting washes of colors, there is a stillness amid its fitted-together sections, as if we were looking at both an image of the ocean and a piece of shattered glass. In fact, as I was looking at Schimert’s watercolors, a most unlikely connection came to mind—Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923), which is often called The Large Glass. It also occurred to me that the glass and ceramic sculptures, with their craggy surfaces and pooling glazes, could be seen both as an echo of the watercolors and their residue, as if the ocean had hardened or molted into these terrains. What ultimately connects the watercolors to the sculptures, however, is the artist’s preoccupation with light, and how to register its different states of immateriality.

The octopus is a creature in which the head and body are one. Philosophically speaking, one could say that it exists in counterpoint to what has been identified as the mind-body problem. In this regard, Schimert’s octopus shares something with the motif of the sperm whale, which Jasper Johns embedded in the vertical lines of the background of his encaustic painting, Ventriloquist (1983). Johns, it should be noted, based his whale on a woodcut Barry Moser made for his illustrations for Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, published in 1979 by Arion Press.

Like Johns’ sperm whale, Schimert’s octopus is a creature whose mind and body are fused together apparently work in tandem. This represents the largely unattainable ideal of philosophers, such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, who wrote about being in tune with one’s surroundings as well as thinking and doing in unison. In that regard, the octopus is a kind of seer, but one whose body is capable of excreting ink and changing both its surroundings and how it is seen (or not seen). It is both the maker and the instrument of its own perception. In works such as Predator and Lurking Octopus it is evident that in her metaphor of octopus-as-artist, Schimert recognizes the artist’s capacity for destruction, and that art is not necessarily a benign presence.

All of these possible ways of recognizing Schimert’s metaphor are the result of her formal mastery. The watercolors can be said to be explorations of the figure-ground relationship. At times, the figure (or octopus) seems to be on the verge of merging with the ground (the ocean). In other works, the shift from the ocean’s blues to the octopus’ grays is distinctly voluptuous, which is further underscored by the rows of suckers visible on the tentacles. But it seems to me that the most important aspect of the octopus’ identity is its body’s ability to secrete ink (or watercolor) into the ocean. By doing this, the octopus can escape detection, become invisible, which seems essential to Schimert’s imaginative understanding of the ideal artist. She believes that the octopus (or stand-in) is capable of disappearing into its own medium, the constantly changing, watery world it inhabits, and becoming one with it.